The beautiful valley of the young river Yarrow by Dean Wood was the subject of more than one poem (see Hampson and Rawlinson), however the world had begun to change in 1847 when Liverpool’s demand for water started its Corporation’s intrusion where the water meandered around Lester mill; but more disturbance and disorder were to come.

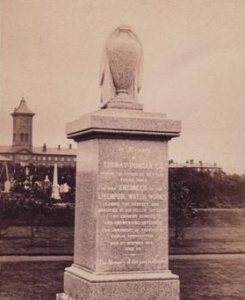

An additional reservoir to the Rivington Pike scheme, starting at ‘the forks’ of the Yarrow, was recommended by the engineer Thomas Duncan in June 1865, and a Liverpool Corporation act (an extension to their 1847 act) allowed yet more compulsory purchase, though this took some time to fulfil.

Three farms lay within the proposed site, all in Rivington, Turners which was two homes, one occupied by the James Bain and Turners cottage, apparently a commodious country home, by the schoolmaster Septimus Tebay, right up to the start of the works. (Septimus Tebay was not the law-abiding schoolmaster you might expect, in May 1871 he was find and made to pay costs for a breach of the peace against James Clayton of Brook house in Anglezarke).

Three farms lay within the proposed site, all in Rivington, Turners which was two homes, one occupied by the James Bain and Turners cottage, apparently a commodious country home, by the schoolmaster Septimus Tebay, right up to the start of the works. (Septimus Tebay was not the law-abiding schoolmaster you might expect, in May 1871 he was find and made to pay costs for a breach of the peace against James Clayton of Brook house in Anglezarke).

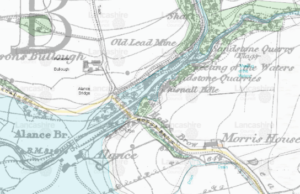

100 acre Alance farm (owned back in the 17th century by Thomas Alance) was at the head of the valley and was home to Joseph Taylor, (he then moved to Morris house and soon passed away). Another substantial property, Jonathon Kershaw’s Andertons was just on the bank, but much of his farmland was to become part of the reservoir.

Press invitations for construction tenders went out countrywide in March 1867 and construction began in earnest in 1868. Three years to the day after Duncan’s recommendation, ‘Fair progress’ had been made, timber was being cut, trial holes sunk on the puddle trench and by new year, 300 men were ‘on the mountain’ where a ‘village had been erected’, stabling for horses etc. But the engineer Duncan had died (his obituary says after a four month period of illness brought on by hard work). By spring 1869 this workforce had risen to 700 putting in two puddle gutters (Turner’s and Yarrow embankments) under the guidance of new engineer Joseph Jackson, and resident engineer Robert T Martin.

The Irish ‘Navvies’ (excavators)

To be true to their role, the temporary Irish ‘village’ in Alance was full of excavators, though due to their more common place of work, canal navigation, they were commonly termed navvies. These people were a Victorian sub-class, perpetual outsiders or non-belongers who lived and worked in ‘muck’. Being a people apart, they tightened their ring against outsiders and clashes between navvies and locals were often violent.

Many local families dreaded their arrival, were terrified of them and despised them, not least because many of them were Roman catholic, (not common nor well accepted in Rivington and Anglezarke), and used brutal language. Women shunned them, children hid from them but many men had a secret grudging admiration for their muscle and might.

Often navvies were family men, who arrived in Liverpool from rural Ireland as young survivors of the famine. Poor wages and squalid conditions in the city’s roughest areas, they saw the chance to dig their way out. An outfit of heavy boots, corduroy or moleskin trousers, shirt, waistcoat and often a bright neck-scarf. They worked in a gang (sometimes known as butty-gangs) of up to a dozen led by a ganger. Employers usually tried to keep nationalities apart, and with Liverpool’s growing Irish population, brought in a huge group or Irish workers.

There were three roles, runners, trenchers and then the excavators. An excavator started life as a labourer, and typically took 12 months to build up the muscle and stamina to shift 20-30 tonnes of muck per day with a pick and shovel. Boys worked with their fathers, brothers worked together, but many left to join a good gang with a chance of better earnings. A gang would negotiate a wage based on piece-work, how many wagon loads of ‘muck’ they would shift. If you couldn’t keep pace, you were thrown out and replaced. A labourer may get a couple of shillings a day, but a good excavator might get 6s. Being drunk, lazy, belligerent might get you a drop in wages by the foreman or at worst, no wages, maybe just a meal token. There is a ‘stone head’ pictured in Rawlinson’s ‘About Rivington’, embedded in the wall of the Yarrow embankment (sadly now badly damaged and barely recognisable) which is reputed to be the effigy of an ill-tempered foreman carved by one of the masons (see below). I sketched the original and to me, the foreman had a pointed chin, moustache and was wearing a cap.

A place to call home

Pay was one consideration, but lodgings were another. A migrant workforce, in the case of the Yarrow reservoir, over 500 people, needed housing in a rural area where there were no rooms to be had, so home was a usually a wooden or sod-hut. A whole gang lived together in one hut which the ganger rented, and he, his wife and kids slept in one side and the single men in the other. One hearth meant the woman of the house cooked for all of them, washed their clothes and sometimes brewed their ale.

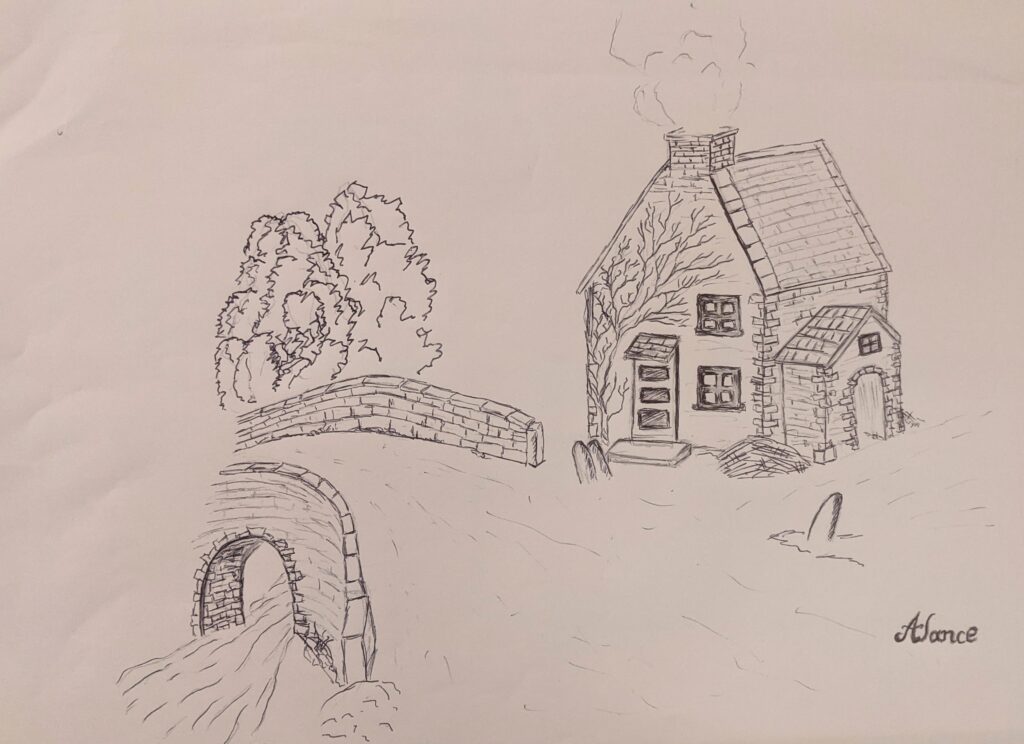

Corporations like Liverpool believed Irish navvies would settle for sod huts, as in 1841 around 40% or rural homes in Ireland were single room mud cabins. Huts weren’t registered as ‘common lodging houses’ so weren’t subject to inspection. The construction involved building a brick chimney and hearth, laying a base of stone and pile 2’ x 1’ rectangles of turf (sod) on top leaving space for a single door and usually a couple of windows. They were usually topped with more sods, or with roof timbers and roofing felt.

From other engineering sites, we know that sod huts could be built in around three days and were best built when the turf was dry, and could even by whitewashed (wet turf meant water ran from the walls into the beds and the roof steamed.

They were commonly 12 feet wide and around 30 feet in length with benches in the living part and hard beds, where could lay in bed and pick fungus in summer and icicles in winter. Cleanliness depended on the woman of the house, and the hygiene of the men living in it.

Leisure Time

It was common to use a nickname, and a navvy with a poor reputation would change his name regularly when he moved on, making tracing next of kin after an accident often impossible unless they had disclosed their real details to their gang. And death was common, both from industrial injury, alcohol abuse and violence. Unable to go into town, for the usual entertainments open to the locals, the excavators main hobbies were drinking and fighting. (I wonder whether their presence fuelled A Eccles hatred of alcohol). It seems from the newspaper reports of the time that their ‘rough’reputation wasn’t unfounded.

On the 19th January 1869, James Riley was returning to the huts at the works from Anglezarke where he had been drinking. He fell into a Delph (quarry) 40 feet deep, and was found by farmer John Taylor and conveyed to the workhouse hospital.

William James Hinde Blackmore of Jepsons in Anglezarke, beerseller, was refused a licence on the 8th September 1869, on the same day that, at 5am, an unknown man aged between 50 and 60 had been found dead at Leicester mill quarry where he had fallen 19 yards from the top (near Jepsons Farm). He was described as a stout man, 5ft 7 inches and respectably dressed in a reefer jacket, dark corduroy vest and trousers and a black silk cap.

On the 4th July 1870. Mr Ogden, a stonemason at the works was violently assaulted.

In February 1871 a man was caught breaking the window of one of the huts and that same month, James Colclough of Rivington was fined 20s for assaulting Police Constable Emslie of Anglezarke. Colclough subsequently defaulted on the payment and was imprisoned for a month.

In March 1872 a warrant was issued against William Cullen of Anglezarke for fighting with Raney Fitch at Rivington

In July 1872, a man named Thadeus McCarney, together with Patrick McCabe and others were drinking at the Broad Oak beerhouse in Heath Charnock and a brawl ensued. The men were separated but between 9 and 10pm the fight restarted outside. Thadues was seen with his hands around McCabe’s throat and at some point in the tumult, McCabe neck was ‘dislocated’. McCabe was described in court as a quarrelsome man and the case was discharged. The judge said of the men “they make their money like horses and spent it like asses”. An additional policeman was to be stationed nearby. Some days after his acquittal McCabe sent a letter to the Chorley Guardian, complaining about an anonymous letter from witness sent to the prosecution. McCabe said, he was the only one present who could write, and he hadn’t written it!

So where was home?

A newspaper article of a visit to the site in December 1873 gives us an amazing glimpse at the life and work of the 480 men and boys and 33 horses employed there.

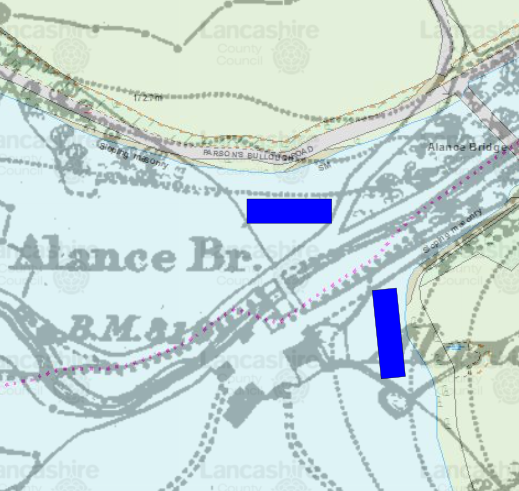

It says that a number of huts were constructed for employees within the boundary of the works at the ‘commencement of the undertaking’. We know from the 1871 census that some were in Rivington, some in Anglezarke. The 1871 census shows ten huts on the Rivington side and another ten on the Anglezarke side.

The writer toured the Rivington huts, behind what had been Alance Farmhouse. It had been renamed the shanty and used as a provision store.

The huts had sod walls (not wood as suggested by Rawlinson), a ‘house part’ with brick fireplace and fixtures, entered through a single door with ‘rooms’ either side. There was an open timber floor, covered with roofing felt. On the left was the ganger and his wife’s room, partitioned from the children’s ‘room’ at the end, on the right was the lodger’s room.

So a temporary village or ‘shanty town’ arrived almost overnight. These ‘villages’ were as prone to outbreaks of typhus, cholera and dysentery as you would expect. Usually new beerhouses, both licenced ones and illicit, sprang up locally and braver locals saw the opportunity to let out a stable, barn or room to lodgers, though the chaps had a reputation for doing a ‘flit’ without paying rent. Lee House in the heart of Leicester Mill quarries, was a beer house known as the Clog inn and run by James Catterall, Blacksmith, and had been such since the earlier reservoir works. John Donnelly was running a beerhouse (and grocers shop) from the cottage at Parsons Bullough. He also had a licence for off-sales. William JH Blackmore was selling beer too, but he was refused a licence due to irregular notice. Interestingly, the Catteralls at Lee House, Halliwells at Parson’s Bullough, and the Blackmores at Jepsons were also letting rooms or cottages to the navvies. Peewit Hall was home to various members of John Donnelly’s extended family, and Abbots Farmhouse and Manor house (high Bullough) were also let to Irish navvies.

Butchers, bakers and grocers saw an opportunity to and set up stalls near camps, or paid regular visits with a cart to make dents in the navvy’s wages. Each man would have his tommy-tin and the woman of the hut would cook his food in it.

The 1871 census gave us a record, albeit maybe not an entirely truthful one, of the names and birthplaces of the excavators.

On the Anglezarke side of the ‘street’:

John Little, and his wife Elizabeth had arrived from Ireland sometime after 1868, and had five children under ten years of age and four unmarried lodgers.

The next hut was headed by Thomas Doblam, but his hut is marked ‘absent on spree’, we can only guess.

Next is George Mackews (probably more likely McHugh) and his wife Catherine (nee McPartlin), and their two young sons, the youngest of whom had been born in Rivington in 1869. Another son James followed in 1872. She catered for six lodgers.

John Trainer and his wife Catherine had come from County Cavan and County Monahan, via Lincolnshire within the last 12 months and had two daughters and seven men living with them including Andrew Sprowl, a married excavator from County Tyrone.

Next door was absent, the occupants ‘travelling’ but let to another Andrew Sproul, 25 years younger than his neighbour, and probably his father.

Patrick O’Brien bucked the trend, marrying a Lancashire lass, Rose, and they had four children and three lodgers.

Another absentee hut next door, as excavator Thomas Jones was absent seeking employment.

Thomas and Mary Ann Cosgrove and their six children plus four lodgers had another empty hut alongside rented to Thomas Cullen, also seeking work. Mary Ann was pregnant with another son Edward, but died soon after her eight child was born there in 1874, aged 40.

Lastly James and Kate Brale and their toddler Mary finish the row.

That’s ten huts, at least sixty people with only six women, twenty children, and nearly 30 unmarried navvies

The Rivington side of the ‘Street’ has another ten huts, and this time, we have numbers, are another 61 residents.

1. Owen and Fanny Quigley and their two sons, and six lodgers

3. Widow Martha Moore and her four children, the eldest being a carpenter, and four lodgers

5. fifty year old Hugh McGravie and his wife Ann had three of his four children working with him. (He was later involved in an explosion)

7. James Patterson was a foreman, with five sons all working as excavators and two lodgers

9. Pat Keelan, his wife Mary and three children, his brother and another lodger

11. Michael and Julia Corner had five lodgers

13. Thomas and Mary Ryan and their two sons and eight lodgers

15. James and Mary Savage, for children and two lodgers

17. Henry and Mary Thomas broke the mould, both being English, and Henry is a housekeeper, but of their three children, one is a mason, another an engine driver

19. John and Jane Dixon and their two daughters, one of whom is only 2 days old, have one border. Strangely John is a coal miner, not a waterworks man.

Obviously this only covers around 120 of the 300+ employees, and we would have to look to Rivington, Anderton and Heath Charnock to find the non-Irish employees.

View from the Yarrow embankment (prior to the road bridge) across to the new Alance Bridge

Accidents

Accidents were common and not always alcohol related. The biggest challenge was the Turners embankment. It required an excavation depth of 165 feet before they men reached rock and could construct the puddle gutter with clay.

On Sunday evening, 14th May 1871 Daniel Strange aged 40 was testing an engine which was pumping water from the puddle gutter when he fell to a depth of 100 feet. His body was found the following day by a man named James Farrell. Unlikely the Irish navvies, Daniel, a Scot, was welcome in the community and had lived with his wife Ann and five children at the top of Babylon Lane near Turners Smithy (the Bay Horse).

When Hugh McGravie (of the Anglezarke huts) was carrying a shovel of live coals through the stone gunpowder store to make a fire in the storekeepers office when a spark lit some spilt powder on the floor and then a 40lb gunpowder barrel. The roof was blown off, windows out and apportion of the stone structure collapsed. Hugh was badly burned and hurled out into the road. Robert Kilpatrick a stonemason was cut badly in the leg, and McGowan, the storekeeper was seriously injured.

On the 25th March 1871 the Bolton evening news reported a serious accident when John Halliwell (of Parsons Bullough) was coming through Dean Head lane, down Hodge Brow over the arched at Alance bridge to Anglezarke where the road meets a sharp incline to his farm. The loaded cart fell over and caught Mr James Donnelly (possibly the brother of John who was renting a cottage at Parsons Bullough) breaking his thigh in two places and injuring his back Donnelly was conveyed home and medical aid given. This is the same Donnelly who was running a beerhouse from John’s cottage.

What happened next

The reservoir never did solve the water shortage issues despite the huge cost and was referred to as ‘Beloe’s dry dock’, named after Mr H Beloe, chair of Liverpool water committee.

In late July 1875, an advertisement appeared in the Manchester Evening news for fifty valuable cart horses, wagons, carts etc. It mentions ten powerful short legged horses that have been used at Rivington in the construction of the new reservoir and sold by order of the water committee.